“ We do not like prisons, but they do not scare us,” Mahienour al-Masry

Looking at the Egyptian political scene in 2014 could make you believe that the Egyptian revolutionary uprising of 2011, at the end of three and a half action packed years, has come to naught. With Abdfel Fattah al-Sisi, former chief of staff and also formerly head of Mubarak’s military intelligence as president, the Egyptian state now appears intent on putting Mubarak’s economic policies and even some of his long time cronies back in place and on silencing all forms of protest, now and in the future. Naturally, draconian measures of repression have been undertaken towards this not too hidden agenda.

Yet to evaluate the outcome of the 2011 uprising one needs to look not only at the current governing caste, but also beyond it, to the emerging forces of resistance. One of the most spectacular and lasting aspects of this resistance has been the powerful presence of women within its ranks. It was a young Egyptian woman, Asmaa Mahfouz who called upon people to come out on January 25th, 2011, and women have been notably present at every stage of the protest movement since then.

In 2011, Tahrir Square was a space where Egyptian women found empowerment to reject the two models that have previously limited their social role. In the Tahrir sit-in, women rejected the pseudo liberation that invites women to only fight for their individual and personal freedoms, to demand that they become active members of a society that continues to be based on exploitation and injustice, where freedom can only mean the freedom to be exploited, to exploit others and to consume to the best of our abilities.

They also rejected the patriarchal model that aims to transform women into domesticated dependent members of a repressive family structure and reduce their social roles to being good wives and mothers. The result was an abundance of women who were full participants in all the activities that transpired between January 25th and February 11 and led to the ouster of Mubarak. In Tahrir women demanded social justice, true liberation and freedom from fear, need, abuse and exploitation not only for themselves but for all. Today, and even though the Tahrir sit-in no longer exists, and the square itself is more often than not circled by army vehicles meant to bar all forms of dissent and resistance, the spirit of the sit-in lives on.

Egyptian women have paid an excruciatingly high price for their participation in political movements of dissent. Since as far back as 2005, the Egyptian police have been targeting women with multiple forms of sexual abuse that begin at the sites of the street rallies and marches and continue and escalate to full-scale rape in police custody and in prison. In March 2011, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces, which was the transitional government during that year, dispersed a small sit in of around a hundred people in the square and arrested several participants. Among those arrested were nine women who were subjected to “virginity tests,” an abusive procedure which was justified as a precaution against potential allegations of rape in custody.

Women activists who continue to participate in public mass events, an indispensable part of any resistance movement do so with full awareness of the risk of being targeted for sexual abuse that raises almost no reaction from the country’s inactive and silent population. Following the ouster of President Morsi last summer, many of those arrested from among his supporters have been women. Credible allegations that they have been particularly targeted by the police for widespread and severely abusive treatment have been reported.

Yet, and in the face of these horrors, women have continued to work for the goals of the revolution and to exercise their right to be fully engaged with the resistance to all forms of repression. In November of last year, a new “protest law” was added to the Egyptian constitution, which was being amended following the ouster of President Morsi by the military a few months earlier. The law in effect bans all forms of protest assemblies, rallies, and marches. Activists have organized several rallies to protest this law and the government has responded and women were still present both at the forefront and among the rank and file of these rallies.

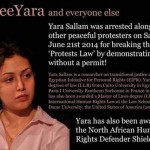

Special mention is due here to Mahienour al-Masry. Mahienour is a young lawyer from Alexandria. She has been active in the resistance to state repression and police abuse even before 2011. Alexandria activists have known her since the protests to the brutal murder of Khaled Said during his arrest by the police in 2010. During the last four years, Mahienour has been incessantly working with and in support of hundreds of others still hope to pursue its goals of freedom, social justice and dignity for all.

Besides organizing and taking parts in protest action, Mahienour has also been visiting jailed activists providing legal and financial support, visiting families of those who lost their lives to the struggle, networking, fundraising, and organizing to give these families both the material and moral support they very much need.

Last May, Mahienour and nine other activists were arrested for a protest assembly that took place in December 2011 outside the courthouse where the murderers of Khaled Said were being tried. She was sentenced to two years in prison. Mahienour’s friends write to her every day, messages that, for now, she cannot read.

She has also recently received the 2014 International Ludovic Trarieux Human Rights Award, which is annually awarded to advocates of human rights. From behind bars, Mahienour has become the proof for many, that something of the revolution of 2011 refuses to be defeated, that it will not all come to naught.

Mahienour Al Masry in jail